Storytelling and compelling anecdotes create an emotional connection and draw people in to your content, but sometimes you need cold, hard facts to help establish authority. Unfortunately, the internet is awash in bad and misused data—and a lot of the bad data is finding its way into marketing content. If the reader notices, you’ve demolished your credibility, and it will be very difficult, if not impossible, to regain that trust.

As a content writer and researcher, I see a lot of bad data and misused statistics out there—and I’m here to help stamp it out. When using data in your content, these are the questions you should ask yourself:

Is there even a source to begin with?

Phantom facts are the data points you see cited in every not-great blog post on the topic. Sometimes, the author doesn’t include a link. If there is a link, it’s to another blog post that also cites the data point without a link or with a link to another blog post—the cycle continues. What content writer or researcher hasn’t fallen down this rabbit hole, trying to find the original source of a statistic to authenticate its validity?

But down the rabbit hole you must go, if you want to use it in your content.

Why do so many people feel comfortable using phantom facts in their content? It’s likely because these “facts” have become entrenched truisms. People feel ok using them without citation “because everyone knows that.” Here’s a great example of an alternative approach.

This writer started with a “fact” that all marketers know: The Rule of Seven. It’s a rule! The writer uses it as a hook to make a larger point that doesn’t rely on the rule’s veracity. In fact, the writer uses the data to share her own opinion.

Note: if you are able to find an actual source—which most of the time with phantom facts, you won’t be able to—gauge its credibility. If the source is credible and the data meet the other criteria of “good data,” then use it. If it doesn’t, dump the data point entirely.

Is the source recent enough?

When is a fact no longer a fact? Or put differently: when is a fact so dated that it’s no longer relevant or worth citing? The answer: it depends on the context.

A statistic taken from the 1980 U.S. census isn’t valuable if you’re writing about today’s U.S. population. If your article is about the 1980s, then it’s good. This is the easy context to address. There’s a clear shelf life for this data point.

Here’s a murkier scenario. In 2021, I was researching an article and found an industry report from 2019 that had perfect data to use. But was that data point still relevant in 2021? I searched high and low for the organization’s 2020 industry report and couldn’t find it. As it happens, this was a biennial report, so there was no 2020 report. So I used a spot-on data point from the 2019 report, but only along with data from other, more recent sources that were consistent with the 2019 data.

Pairing an older source with a recent one that reinforces the same point invigorates the credibility of the older information. Source-pairing is also a useful tactic when one of the data points is behind a paywall, as is the case in the screenshot below from a Zapier blog post. (Yes, if the best data point is behind a paywall, still link to it.)

If you’re writing about something that can change quickly, then stick with the most recent data. This covers writing about trends, effective strategies and tactics today, and where the greatest threats and opportunities lie.

On the other hand, if you’re talking about an established principle, then an older source could be more authoritative than some new theory. Robert Cialdini published Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion in 2008, but it still holds up. So do Aristotle’s treatises on ethics, for that matter. In my opinion, both good sources.

What’s the quality of the source?

Google likes high authority sources. So do people. But credibility can be subjective.

Some names have long-established reputations: think of surveys and research by Pew and Gallup. Google and humans alike will trust these kinds of sources.

Even better is a well-known name that also shares its methodology with readers. Everyone’s heard of Verizon, but does that mean we should automatically believe whatever data they share in an industry report? No, and they don’t think so either. That’s why they detail their research methodology in their widely-cited, annual data breach investigations report (DBIR).

This is just a snapshot of a small section of their methodology appendix, which you can find here.

Not every credible source needs to be a known quantity. But if you find an unknown source with little earned authority behind its name, access to their methodology is crucial. You don’t have to detail their methodology in your content—an interested reader can follow your link and dig into it for themselves—but you need to read it to be sure you can trust the source you’re linking to.

Are you accurately representing the data?

Sometimes, the original data points are true, but the writer misrepresents what the source says. This is bad. The writer and brand that misrepresent what the data says or means will come off dodgy or not very smart. Neither is a good option.

Promote and publish your content with automation

A good-faith example is when the writer doesn’t accurately frame the research or statistic. Let’s say a survey of small business owners asks about their financial management. Instead of writing, “30% of all small businesses struggle with cash flow,” it’s more accurate to write “30% of all small business respondents reported they struggle with cash flow.”

If you’re citing a study that used more rigorous research methods than a self-reporting survey, you can use stronger language. For example, if you’re citing a cybersecurity report that investigated data sets of actual breaches, you can write something like “90% of cybersecurity attacks begin with an email,” if that’s what the research shows.

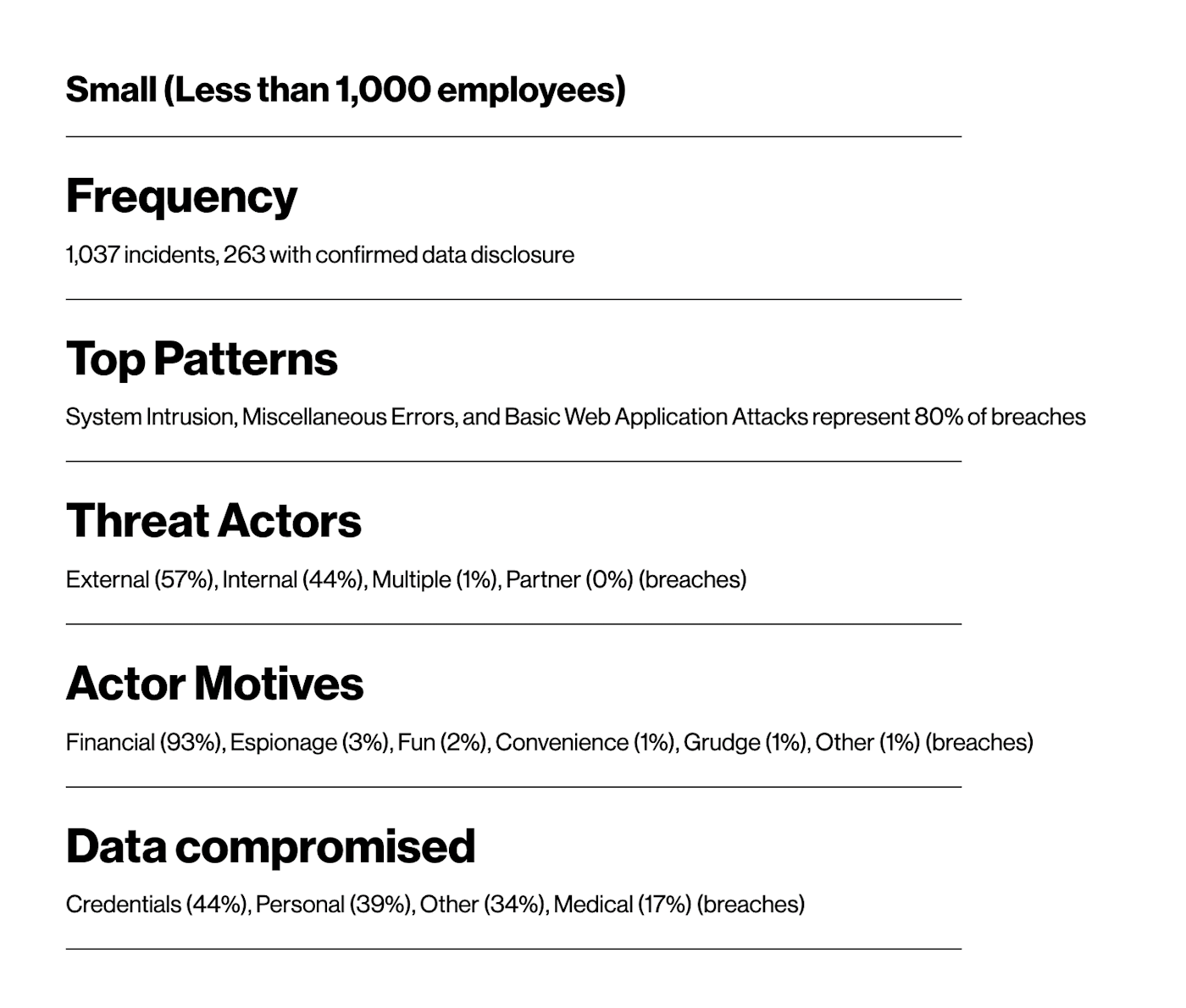

Returning to the 2021 DBIR report, I’d feel comfortable writing, “According to Verizon’s 2021 DBIR report, nearly half (44%) of the threat actors attacking small businesses come from inside the house.”

Do you understand the data?

A lot of unintentional misuse of data and findings happens when referring to academic research and studies. For starters, the language in the abstracts can be pretty tortured (don’t even start with the methodology or results sections). Plus, folks often rely on the press release about the study rather than the study itself, or pull from the hypothesis section rather than the results section. This article on the causes of bad science reporting details the issue nicely, and I highly recommend it if you often cite academic research.

If you find an academic study chock-full of perfect data points, consider these questions:

-

Does your audience want/care about the academic research, or will presenting the findings precisely and accurately become a tangent or take attention away from the larger message you’re trying to share?

-

How valuable/necessary is this data point to the central message/goal of the piece?

If citing the academic study will cause too much headache, leave it out. If it really feels like high-value validation for your article, then get a second opinion. Talk to a subject matter expert (SME) if you’re not 100% rock solid that you’re understanding the results right and can present them accurately.

I often write about architecture, engineering, and construction. When I come across research touching on chemical reactions and physical properties of materials and methods, you best believe I talk with internal SMEs to make sure I cite the research properly.

Another option is to find a separate reputable source that delves into the study and link to that article as an intermediary. Example: the secondary source (Fast Company article) used in the Zapier blog post I pointed to above is all about a university study examining data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Is the source a competitor?

I know my fellow content marketers share my pain here. You find the perfect data, and you can’t use it because the source is your (or your client’s) competitor. Here are some options:

-

Ask around to see if you have any internal data you can use instead. If your competitor has it, it’s possible you have it too. (If you’re working for a client, ask them directly.)

-

Use it as a starting point for research for similar findings by other sources.

-

If it’s just too good and too on point, ask some other stakeholders (or your client) how they’d feel about linking to the competitor. In some cases, it might be worth it.

Does the data point add value?

Data points, citations, and links aren’t always necessary.

Sure, bad reviews impact sales. We know that. Everyone knows that. Linking to a generic statistic telling us that doesn’t add any value to your content.

If you have more nuanced information, that’s a different situation. Did you find credible research that quantifies the revenue impact differential between having a below four-star or above four-star rating? That’s worth sharing, and you should link to it. Otherwise, you’re adding fluff, like word-stuffing your content. Don’t do it.

Lies, damn lies, and whatever

There’s some cliche about statistics, often attributed to Mark Twain. Those in the know will confidently state that Twain was quoting British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli. Further investigation (here, here, and here) reveals that Disraeli was likely not the original source either. Seems a fitting conclusion.

The point of citing data in your content is to bolster the credibility and authority of your brand. So take the time to do it in a way that helps achieve that goal—and doesn’t undermine it.

Need Any Technology Assistance? Call Pursho @ 0731-6725516